I’m pretty sure that a lot of puppies think that’s their name, because most of them hear those three words more often than any others. (Some puppies hear another interrupter. The hissing noise Cesar Milan uses is popular. Imagine thinking THAT was your name!) The problem is that while interrupters may prove effective in pausing unwanted behaviors, they only constitute an interruption. If we end at StopNoDon’t, the puppy will either resume their unacceptable behavior as soon as we turn our back on them, or will find something equally — or more — unacceptable to do. After all, there are only three categories of object in the world — Food, Fun, or Boring. And you can’t categorize new objects until you’ve tried to eat them or destroy them. It’s the canine version of the scientific process. So, how to handle these situations? There are a few basic skills you need to build independently of the urgent situation. One is the Trade, aka Give. You teach the pup that if they let you have what they are investigating, they get yummy stuff back and maybe their original object as well. Another is a Recall. For some puppies, the simple act of running toward someone is enough to banish all thoughts of other fun from their mind. (For others, it’s just an interrupter.) Sit is another great skill to have. It’s hard to be naughty when you’re sitting. Then there are two skills for the human. The first is remembering to Always Have Something Amazing In Your Possession. Whatever you have needs to match or exceed the value of whatever your puppy might find. For some dogs, that’s easy — FOOD wins every time. For others, it might be a ball, a tug toy, or a stuffie. The other skill is more complicated and takes some practice. That is Being Able To See And Train What You Would Rather See Happen. That’s a hard one. It takes a lot of practice. For me, I have to close my eyes and SEE how I would rather have the scene look before I can train it. Sometimes we need Professional Help to make this happen. A puppy example of this process would be chewing on everything. Sometimes I’m a little slow on the uptake or too tired to pay attention. That’s when I find myself interrupting the chewing six or even eight times before I realize I have a training issue. I will hear the chewing, usually in another room, track it down, interrupt it, move the puppy, rinse, repeat. It’s generally not until the target of the chewing is either my gliding rocker or the handle on the LaZBoy recliner that I actually focus on the problem. The first step is to contain the puppy. This usually means lugging ex-pens in from the garage to establish a containment unit to use when I don’t have two brain cells available for puppy monitoring. Into the ex-pens go appropriate chew toys. Then the puppy gets outfitted with a harness and leash, and I get to carry two or three chew objects with me wherever I go. The pup is either leashed to me or contained in the ex-pen. Any attempts to chew on inappropriate objects while leashed to me are interrupted by a recall, which is rewarded, and redirected by presenting an appropriate toy. Chewing an appropriate toy generates praise and intermittent treats (which gives me a chance to practice Trade For A Treat, as well). Refusal to chew an appropriate object or fixation on the furniture earns some ex-pen time. It may take six hours (Border Collie) or six months (Labrador), but the basic process is effective. An adult dog example would be my boy Apollo. When he came to me, Apollo, a Golden Retriever, was pretty sure that the only way to get a human to notice him was to put part of the human’s body in constant contact with part of his mouth. While it was cute when he held my hand, I really couldn’t spend my life with his tongue stuck to my arm or leg when my hand was unavailable. I really had to put my Trainer Thinking Cap on for this one. I hate having to do that. I realized that the solution was to put something else in his mouth, so I went out on Amazon and bought literally a dozen small Outward Hound firehose toys. When they came, I distributed them liberally about the house and made sure I was always armed with at least one. As soon as the gaping maw opened, I put the firehouse toy in it. Then I pet Apollo. I stopped petting him unless he had a firehose (or other toy) in his mouth. After a few days, I started offering the toy, saying “get your toy,” and made SUCH a fuss over him when he took it. He was positively gleeful! It was a short step from putting the toy IN his mouth to tossing it on the floor in front of him, then to being able to just remind him to “get your toy!” I think it took about two weeks for him to start spontaneously bringing his toy when he wanted attention! I realize that these are two pretty straightforward examples. There are a lot of more complicated scenarios that involve things like teaching your dog to run to their bed when you are woodworking in the garage or cooking dinner, or talking on the phone. Or teaching them to sit and wait while you get the package from FedEx at the door, or to run to you instead of chasing the cat. With a little (a big?) bit of creativity — and maybe some coaching! — it can be done!-

0 Comments

A while ago, I wrote a post about how I feed my puppies. I think it is time to address how I feed my adult dogs. For my young, healthy adult dogs and my older dogs without dietary restrictions, my base diet is a canned food. I purchase canned foods labeled “complete and balanced” and “96% meat.” I always look for foods that only contain one protein source per can. I try to avoid carrageenan and guar gum as stabilizers, preferring agar, which I think is a better prebiotic. I typically buy by the case, and I try to make sure I have at least 2 different foods that each dog can eat, which means I’m usually buying four cases at a time. As with the puppies, I try to use whole cans at each meal. Unfortunately, I often end up with someone whose bowl is going to be calorically deficient, so I have to have either a high-protein kibble (I buy 4 lb bags, usually Instinct or Nature’s Logic) an air-dried jerky style food (Ziwi Peak, Zeal, Only Natural Pets), or a freeze dried rehydratable food (all meat like Primal, Liberty or Rawbble, or meat and veggie like The Honest Kitchen or Spot Farms) to make up extra calories. For my older dogs and my inflammatory bowel brigade, my cart looks a little different. My base diet for them is almost always a raw food, usually Primal, Tucker’s, or Bones & Co. I do commit the blasphemy of gently cooking the patties for my dogs. Their slow cookers are broken — I figure they need the extra help with digestion. Any extra calories are typically either a freeze dried chunk or meat chip food. I try to avoid vegetative matter for these guys. All of my dogs go to training classes. (We sometimes even practice at home!) Training, of course, means food, so just like with the puppies I have a constant supply of special foods to pull from. I’ll usually use a combination of meat chips with freeze dried chunks and carry a small bag of chopped cheese or a sausage-style treat like Happy Howie’s. When more of my treats are complete and balanced, it’s easier to cut back on meals if waistlines start to increase and ribs disappear…  I was having an email exchange with a client about her kitty recently. Her kitty has has some recurrent issues, and all of the current research points toward recurrent problems in cats being secondary to stress. The problem is… my client wasn’t “seeing signs of stress” in her cat. Which brings up the question — what does a stressed cat look like? The answer — a cat. The problem is that as both predators and prey, with an extreme dependency upon maintaining their territory, cats are incredibly adept at looking normal. The only signs that most of us see when our cats are stressed are typically things like changes in play behavior, changes in resting spots, becoming a “picky eater,” or inappropriate elimination. Eventually the physiologic changes associated with chronic stress in a cat become vomiting and diarrhea (inflammatory bowel disease), hair loss from overgrooming (psychogenic alopecia), aggression (directed at other cats or any member of the household), recurrent upper respiratory infections (usually due to herpes), and recurrent urinary tract infections. What we forget about our feline companions is that, unlike dogs who have been selectively bred for generations to tolerate close confinement with people, most of our cats have only been bred to be small. Admittedly, the purebreds (the historically older breeds) seem to tolerate civilization somewhat better than our standard mixed breed kitties, but even many of them suffer from stress-related diseases. All of this leads to the question — What do you do about a stressed cat? The ultimate answer would be “add potted plants to the indoor landscape and set mice loose indoors.” This plan carries the unfortunate drawback of resulting in the deposition of mouse waste in unhygienic locations, as well as the occasional distribution of mouse parts throughout the house. A more acceptable answer is to create opportunities to do cat things, like hunting, in directed ways that are acceptable in a human household. For a cat who is a novice indoor hunter, this means distributing small portions of food in multiple locations throughout the house (or one room, if there is a dog). For the more experienced cat, the bowls can be food puzzles. (Google “No Bowl Feeding System” to see videos of one clever example.) The creation of a more cat-friendly territory can be achieved by strategic placement of scratching substrates as well as cat trees (the taller, the better). Adding resting spots where the cat is in an elevated position and feels concealed (but can easily peek from it and spy) is great. And, of course, the strategic use of Feliway as a diffuser, spray or collar can be immensely helpful to cats who are showing signs of stress (but only in conjunction with the strategies outlined above). If you live with a member of Felis catus, I encourage you to explore one or more of the following resources (in no particular order): The Trainable Cat by John Bradshaw Think Like A Cat by Pam-Johnson-Bennett Does My Cat Hate Me by Amy Shojai Beyond Squeaky Toys by Nicole Nicasio-Hiskey and Cinthia Alia Mitchell Total Cat Mojo by Jackson Galaxy Catify to Satisfy by Jackson Galaxy Catification by Jackson Galaxy Cat Mastery by Dr. Tony Buffington (free ebook available at the website below) The Ohio State University Indoor Pet Project (plug it into the Google machine, the web address is longer than the description) (BTW, my client diligently and enthusiastically embraced de-stressing her cat after our exchange, and the medical issues have improved dramatically.) Once in a long while, usually when we are taking about something that their dog does that bothers them, a client will tell me that they “tried training on” their dog, “and it didn’t work.” That phrasing always sets me back a bit, because it demonstrates a limited understanding of what “training” is, and also of what dogs are capable of doing.

Training is the process of building a vocabulary of signals that allow the human handler to communicate to an animal, quietly and efficiently, what behaviors are desired. Training is not a one-way street —training also involves the human handler learning to “read” the animal, and sometimes teaching the animal cues the animal can use, so the human can tell what the animal needs and what works for the non-human partner. People who say that “training didn’t work on” their dog have an idea that training is essentially a process of installing “sit” and “down” buttons to control behavior. This view sees training as a finite process with a starting point and an end point, often with no maintenance or development afterwards. Training can be that, if we want, however it does take an expert technician to install those buttons and keep them from sticking. Even when installed by an expert technician, those buttons will usually stick without maintenance. It really is more fun to approach the training relationship as something you build/do WITH your dog rather than just a procedure you do TO your dog. People often ask me if “old dogs can be trained.” I suppose this question arises from our emphasis on puppy classes and early learning, as well as on the tendency for institutions like Guide Dogs for the Blind to use their own puppy rearing protocols. There is also a strong bias in our society towards putting young dogs into training for various jobs and dog sports. It would be of benefit to remember that part of the reason for using dogs started as puppies for these jobs is that the dogs’ training represents a significant investment in time and money, and the greatest return on that investment is achieved by getting an early start. It is also faster and easier to habituate a young dog with few expectations to their eventual work environment than it is to habituate an older dog. This doesn’t mean that older dogs CANNOT learn. They do, however, often take longer to reach proficiency at complex tasks than younger animals, or dogs with lots of learning experience. Human beings learn throughout their lives. We establish new relationships, read books, learn new words, acquire new skills and refine old ones all the time. If there is a payoff in learning something new, we will do it. It may be more difficult as we age to remember new information, but if the information is important — or repeated often enough — we remember. The same holds true with dogs. If we make new information or new skills important enough to them through practice and payoff (read: repetition and reward!), they will eventually “get it.” Dogs who have a lot of practice with early learning are more skilled at acquiring new information/skills than dogs who have had very little experience with training. However, if we are kind and consistent (and persistent!) and make the behaviors we want PAY for the dog, even an arthritic 14 year old dog with vertigo can earn a title in Nosework. So… the next time you are frustrated because your six year old exuberant Labrador nearly takes down Grandma in a paroxysmal frenzy of joy or your nine year old terrier threatens to break the window in an urgent need to eat a cat, remember that with patience and persistence (and possibly professional help) you CAN teach your dog… to do something ELSE instead!  Most of us are experiencing some form of pandemic-related stress right now. We have all had our routines disrupted, even those of us who are considered “essential workers” and still get to go to work and have social contact there. We have lost our usual day-to-day contacts and activities, and are now restricted in how often we can go out, when we can run errands, etc. Add to that the generalized anxiety many of us share with respect to the future and it’s easy to feel like our lives are out of control. Welcome to the world of your dog. Or your cat. Or your bird or goldfish, for that matter. We all have a taste now of what it feels like to have an external force that is beyond our control, determining where we can walk, when we can walk, where we can eat, and what recreational activities are available to us. Our household companions grow up with these restrictions. However, think about how unsettling it must be when their regular daily patterns change. Every time our work schedule changes, or we alter our exercise routines, move to a new house, add another family member or pet, rehome an animal… Some animals are very adaptable and “go with the flow” even when accommodations are not specifically made for them, but many cannot. They feel threatened by the new level of unpredictability that is introduced into their lives with change. These animals sometimes exhibit destructive, passive, or aggressive behaviors as a result of their stress. We may mistake these behaviors as “acting out” because our pets are “angry” when, in reality, they are trying to soothe or protect themselves. Have you been snappy with your partner, felt like staying in bed all day, not even been able to decide what to eat, or just wanted to PUNCH SOMETHING? If so, you know exactly how stressed pets feel! All of our pets are”captive species,” a term we used to reserve for wild animals in captivity. Please let your own experience as a “captive species” during the pandemic inform your view of the world your pets inhabit. Their lives will be better for it!  What is pre-anesthetic screening? “Pre-anesthetic screening” is the term we use to describe tests we use to assess your pet’s fitness for anesthesia. At Integrative Veterinary Care, our standard pre-anesthetic screening is comprised of a small blood chemistry panel to look at basic kidney function and a few other indicators, a complete blood count which allows us to see whether your pet has adequate blood platelets (cells involved in clotting!) and red cells (which carry oxygen), and an ECG (also called an EKG) to assess heart rate and rhythm from the heart’s perspective. In some cases, we need to run an expanded panel, thyroid level, or do chest radiographs (x-rays) to assess heart size and shape. Why do pre-anesthetic screening? In the young, overtly healthy pet, we run these tests to look for congenital or developmental anomalies that are invisible on physical examination but which may make anesthesia unnecessarily risky for your pet. One example would be the case of congenital kidney disease that I identified in a 6 month old Maltese who was supposed to be spayed. We had no idea that her kidney values would be 2-3 times normal, because she was running around and eating and drinking like any other puppy. Her owners decided to forego the risk of surgery. In the older pet, pre-anesthetic screening can unearth issues we had no idea about, but which need to be resolved to minimize anesthetic risk. A fairly common finding is a cardiac arrhythmia called ventricular premature complexes, which can be associated with underlying disease and which, if frequent enough under anesthesia, can be fatal. We have also identified “heart block,” where the electrical impulse is prevented by some anomaly from travelling smoothly from the atria to the ventricles, preventing appropriate changes in heart rate to maintain adequate blood flow to the tissues in the event of a change in blood pressure, etc. In one case, we identified a potentially fatal arrhythmia that was secondary to a urinary tract infection! The bottom line is that the more information we have about your pet’s physical state, the better job we can do at making anesthesia as uneventful as possible.  My dog or cat (or rabbit, or chicken) spends the day outside… If your pet spends the day outside, it is possible to keep them safe even in very hot weather, as long as they are healthy. Healthy animals with normal mobility are pretty capable when it comes to keeping themselves as comfortable and safe as possible if provided with appropriate resources. Be aware that pets with short, flat faces (brachycephalic animals) or conditions that affect breathing (such as laryngeal paralysis) may be at risk of overheating when the temperature rises above 80 degrees Fahrenheit, even with appropriate shade, water, etc… Shade Shade is crucial. If your pet is outside in hot weather, make sure that there is an area available for shelter from heat that is open to moving air and provides an area of all day, full shade at least twice as large his or her bed. This shaded area must be protected by a wall, fence, double layer of shade cloth, or reflective space blanket on the south side to prevent sun exposure from the “hot” side. There must also be an overhang, which can be a roof, double layer of shade cloth, space blanket, pop-up shade structure, or mature tree. Water needs to be available in this fully shaded area, ideally positioned near the center of the “wall” or in a corner to prevent exposure of the water dish to sun and excessive heat. Rabbits with outdoor run areas may appreciate an artificial burrow, which could be created using retaining wall bricks for walls and a wide board to create a roof, which can be covered with dirt. The entrance should be north-facing, and shading the area is ideal. Water Provide at least twice as much water as you think your pet might need, which means at least 2.5 quarts (10 cups) of water per 25 lbs of dog, and 2 cups of water per 8 lbs of cat or rabbit. Remember that larger amounts of water will warm up less quickly, and excess provides “room for error” in case your pet steps in the dish or an unexpected visitor (raccoon, cat) comes to tank up! Automatic watering systems are a great idea, with some caveats. It is essential that the entire unit be shaded from the faucet (or tank, if the system is gravity-fed) to the dish or sipper. It is essential to test all outlets on such systems daily to make sure that water flow starts and stops like it is supposed to, and to check both the line and outlets for leaks. Check the outlets daily for debris or build-up that could affect the function of the unit or palatability of the water. Make sure that outlets are cleaned thoroughly at least once weekly. It is prudent to have a second bottle available to small mammals who rely on LIXIT-style bottles for water, in case one unit drips and goes dry. Rabbits and chickens may not drink enough when it is hot, leading to dehydration and intestinal distress. Electrolyte preparations are available for both species. When electrolytes are used, only water with electrolytes should be available. Adding probiotics to the animal’s regimen may also help prevent intestinal distress. Probiotics administered in water are available for rabbits and for chickens. If your dog is prone to stop drinking with stress, offering diluted bone, chicken, or beef broth twice daily may be helpful. Alternatively, mixing a small amount of meat baby food or other pureed meat into water may promote water consumption. Never leave broth or water with meat mixed into it out for more than an hour before discarding the remainder, or bacterial growth may cause intestinal problems. Flavored water may also be attractive to insects, especially flies. Cats may be encouraged to drink more by offering water in a recirculating fountain, or simply by placing water in more locations, especially near favored resting spots. Misters Mister systems can be a great way to keep an area cooler. I do recommend putting them on a timer to prevent the formation of a mud pit or wading pond. It is acceptable to have the mister spray part of the shaded area, but the entire area should not be treated in case your pet needs a dry space to rest in. For rabbits housed in hutches, or chickens, misters can be mounted on the roof of the hutch or coop, on top/outside of the animal’s living space, to keep the roof, and thus the living area, cooler. Never put misters directly on the animals or where their food or bedding will get wet to minimize the risk of mold growth, fly/maggot exposure, etc. Ice Some animals like their water cool. Putting ice cubes or frozen, hard-sided cooler packs in the water dish helps keep it cool. If you do this, do provide 2 water containers, one with and one without the ice, just in case your pet needs the water to be closer to the ambient temperature in order to drink. Dogs and chickens get tremendous enjoyment from ice blocks with frozen food treats inside. Both species like chunks of meat, fruits, and vegetables in their ice blocks. There are containers complete with platters that you can use to make ice blocks, or you can use your own plate or pan for serving. Rabbits may benefit from placing a frozen bottle full of water in their “indoor” area to use as an air conditioner. Some rabbits will snuggle up to the bottle directly to cool down. Any time you use ice, whether it is contained in plastic or open to the air, it is essential to keep the area around the ice clean. Bedding or food that gets wet, whether due to melting ice or condensation forming on containers, needs to be removed and replaced each evening. When the weather is warm enough that we are worried about keeping our pets cool, mold and bacteria can begin to grow within hours, and wet or musty bedding and decaying food are highly attractive to insects and rodents. Garages as Shelters If your pet lives in the garage or has shelter there during the day, a few precautions are necessary. It is never a good idea to leave the front garage door partially open for ventilation – a strategy commonly employed by dog owners. One problem with this technique is that while you may be able to leave a crack that your dog cannot get out through, other animals on the street may be able to get in. Even if other animals don’t get in, your dog will likely experience barrier frustration as he watches other dogs, cats, people and cars pass by, which leads to nuisance barking and aggressive behavior. Newer, non-wood garage doors are also slightly flexible, and I have seen a large dog force his way through an aluminum door by exerting pressure under the center of the door, bending it several inches to escape and charge another dog. A better strategy is to prop open the door into the yard, which can be protected with a screen if necessary. A pet access flap can be installed in the wall near the walk-through door, if needed. Windows can be opened for further ventilation. A fan placed in a window or hung in the doorway will provide air flow. A swamp cooler or small portable air conditioner can be used to maintain a more constant temperature. Cooling pet beds can also be placed in the garage – they tend to be UV light sensitive, so outdoor use is not generally recommended. There are, however, a number of new cooling beds made of novel materials which are designed specifically for indoor/outdoor use. (Look at “cooling beds” on the In The Company Of Dogs website.) Wading Pools Dogs of all sizes and shapes who enjoy splashing in water will like having a wading pool. I prefer the more expensive kiddie pools with textured bottoms. (I have had the same $35 kiddie pool for almost 20 years!) If you provide a wading pool for your dog, be sure that it is placed in an area where splashed water will drain and mud will not be a problem. The pool should be drained every 3 days to prevent mosquitoes from breeding in the water. The wading pool should NOT be the only source of water available to your pet – make sure that plenty of water is available in an appropriate container, as outlined above. Other Ideas A few web searches will turn up dozens of ideas for using solar fans, shade material, and even household items to help keep your animals cool. Do keep in mind the safety and sanitation needs of your specific pet. Beds which are appropriate for a well-behaved, mobile dog may be inappropriate for a crazy chewer or a dog with urinary incontinence who might get stuck trying to get up. Solar fans, appropriately placed for ventilation, might help cool your birds, but beware of the avian tendency to pick at cables and the possibility of kicking up dust with the breeze. If you have an idea and you are just not sure about safety, call your veterinarian’s office and ask – or email a sketch or photo of what you are planning! I know it happens and I understand.

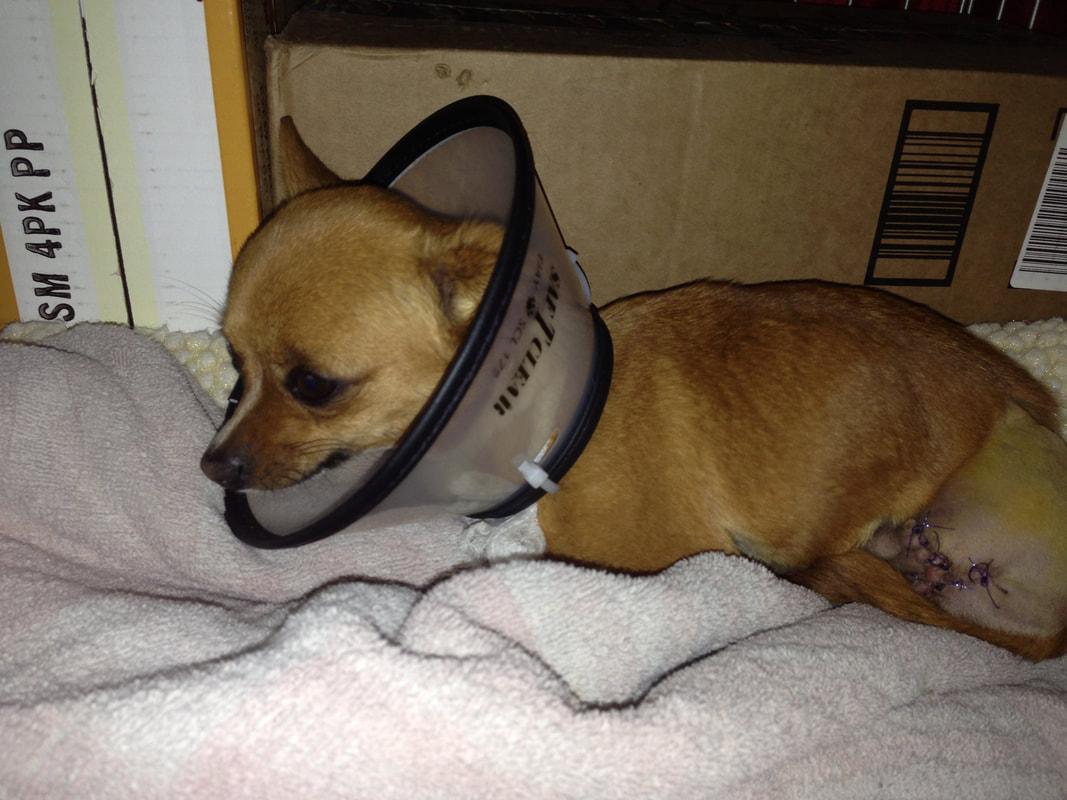

Your cat gets into a fight, your dog comes up limping, your rabbit starts sneezing, your chicken just doesn’t look quite right… so you wait “a few days to see if it gets better.” Sometimes that’s OK, sometimes it’s not. The problem is that I cannot necessarily give you any good guidelines for telling the difference. Sometimes it’s not even possible to tell you whether or not it’s OK to wait when you call us. And while waiting may save you an exam fee and “a wasted trip,” sometimes waiting costs more money and has an adverse effect on your pet’s outcome. One example is Midnight, the limping cat who got into a fight with a neighborhood bully almost a week before coming in. The swelling in his leg, which started the next day, improved with time, but Midnight was still unable to use the leg. The family was unable to appreciate that the swelling happened to be directly over a complex joint, and that the joint had been penetrated. By the time Midnight came in, the abscess had ruptured and was dripping joint fluid and pus. A situation that could have been treated within the context of an office appointment with 2-3 weeks of antibiotics, and a follow-up appointment, if he had been seen the day after the fight, required lavage and repair of the joint capsule, placement of a drain under the skin and a flesh wound repair, and 2 follow-up appointments with 6 weeks of antibiotics. Another example is Harry the sneezing rabbit. Harry had been sneezing for about a month, and his appetite and activity seemed to be normal, but the sneezing was becoming more vigorous and more frequent. Since the change had been so gradual, his family failed to observe Harry’s progressive weight loss and the change in his stool from normal pellets to dehydrated little rocks. When Harry came in, he was underweight, had a runny nose, and he was developing pneumonia. After a week of antibiotics, his family realized how sick he had been when they saw his activity, appetite, and stool return to normal. If you see your pet do something, like jump off the couch or get into a fight, and they seem painful or even just “off” and aren’t basically normal the next day, bring them in for an exam. If your dog misses a meal or vomits once but seems OK otherwise, go ahead and watch for a day or two, but make a note on your calendar to help you keep track of when it happened. If your cat misses a meal or vomits, call your veterinarian to see whether you should watch him or bring him in. Cats should not skip meals, and vomiting more than a few times a year can be an indicator of underlying problems. If your rabbit, guinea pig, rodent, or chicken (unless she’s molting) misses a meal, call. These guys should never stop eating – if they do, there is a problem. Anything else that your animal companion does that is abnormal, put on your radar. If you notice your pet doing it a third time, call your veterinarian. An incident that may not be a huge warning signal for some animals may be a problem for your own pet, depending on his previous history. And you, as the caregiver, know better than anyone what that history is.  You may not think so, but that flabby tabby sleeping on the couch probably has stress. Really. Consider how cats were designed to live, inhabiting an acre or more, primarily solo, occasionally interacting with another cat with an intersecting territory, eating mice and/or birds. (It takes a lot of mice to feed a cat – all of that hunting takes a lot of time.) Maintaining their territory and protecting their resources is essential to survival. They are naturally vigilant and neophobic (afraid of new things), and give suspicious objects and individuals a wide berth. If there is too much stress in a neighborhood, they move. Now consider how indoor cats live with us. They are usually confined to an area of less than 2000 square feet, in close proximity to other individuals without the opportunity to select their roommates, sharing potty areas, sleeping spots, food, and water. Their environment may change at random (new furniture, new odors, favorite items stolen, strange people knocking down walls and altering countertops, etc) and they have no control over the access of other animals to the borders of their territory (windows, doors). The list of stressors can be endless. Combine the elevated stress hormones with an endless supply of high-carbohydrate dry food (spaghetti with meatballs) and an almost empty calendar of events, and it’s no wonder most tabbies are flabby! While this lifestyle does protect our feline friends from being hit by car, bitten by dogs, getting lost, and a host of other bad things, the obese and sedentary lifestyle comes with a host of negatives of its own. There is an intricate interplay between stress hormones, obesity, and inflammation that can influence pancreatic health and diabetes, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis (formerly known as Feline Urologic Syndrome), and probably every other inflammation-prone tissue in the body. There are also behavioral consequences of this lifestyle, including urine marking, inappropriate elimination, inter-cat aggression, and aggression redirected toward humans, other animals, or the environment. So what can you do? The most important thing to remember is that cats have less stress when there are more resources. Not more in bulk, but more in terms of access points. A larger number of resource clusters allows cats to exist in a smaller territory. Food: Choose a high-protein dry (unless your cat’s medical status dictates otherwise) to supplement a canned base diet. Canned foods should be without added carbohydrates. An extensive review article published recently in JAVMA indicated that the protein content of the food drives water consumption and influences a number of other factors which are beneficial to urinary tract health, gastrointestinal health, and weight management. Dry food should ideally be distributed in small quantities around the house, either in bowls or in food-dispensing toys. Food can be elevated on a perch, on the floor, under the bed, in a closet… Or hidden under a box. The cheapest food-dispensing toy ever is simply a toilet paper tube with one end closed. Spreading out food like this decreases stress in multicat households and allows the cat to engage in some purposeful hunting behavior, mimicking a cat’s wild feeding pattern. Litter boxes: Even a cat living solo may need more than one toilet, especially if the cat is arthritic or the house is especially large. Split level homes should have a litter box on each level – think one litter box per shared people restroom if you only have one cat. Multi-cat households need even more – a good guideline is one more litter box than you have cats, but here it gets tricky. Two litter boxes side by side, with no divider, is really one restroom with 2 toilets and no privacy. Kitty stress will be reduced and litter box access will be improved if the litter boxes are at least separated, and are arranged in a manner which prevents one cat from guarding access to them all at the same time. Scratching posts and perches: People have people furniture in every room of the house. The cats should have some furniture, too – at least in shared areas. Scratching posts should be somewhat spread out, ideally with one per cat because the posts really are territorial markers. I personally find the combination kitty towers to be attractive to the cats, attractive to the people, and effective. Perches do not have to be limited to kitty towers and the tops of posts, however. Beds on the corner of a desk, on an accessible shelf, or in a window work well. The more cats you have, the greater the need for multiple elevated perches. Elevation provides the cat with a sense of safety and security, and in a multi-cat household reduces the likelihood of agonistic encounters. Petting and play: To a great extent, your level of interaction with your cat will be dictated by the cat. However, your cat needs some interaction every day. Cats who “don’t like to be petted” may have legitimate pain issues which should be addressed. That being said, most cats are up for a good head rub now and then. Cats can be taught to accept grooming, if you are careful, use a matt rake, and keep sessions short. “Play” for cats can vary greatly, from actively running and jumping after a wand toy to simply watching an object move. If you keep play sessions short, and offer them often, even pretty lethargic cats can be induced to at least throw out a few swats now and then. Wand toys and laser pointers are the most popular toys among cats. Outdoor access: For some cats, a little taste of the outdoors can make a big difference. There are a number of “window seats” designed for cats that can be installed even in rental units to allow your feline companion his or her own bay window. There are also outdoor units designed like hamster habitats that allow you to create a series of “kitty tubes” outdoor. Some companies make kitty kennels that can be placed outside a window fitted with a cat flap to allow outdoor access. There is often a concern about other cats having access to your cat through the mesh of these enclosures. The kitty kennels can be protected by strategic placement of a few Sssscat units. Motion-activated sprinklers can be used to protect larger areas, like the perimeter of a yard. In reality, as long as direct cat-to-cat contact, with bite wounds occurring, and access to areas used for potties by outside cats is restricted, the risk to your housecat in having this kind of restricted outdoor access is minimal. In most cases, a few simple adjustments to the environment can make a huge difference in kitty stress. |

AuthorsDr. Brenda Mills and staff members Archives

January 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed